Kickstarter provides the aspiring creator with some sobering statistics on campaign success rates. Since Kickstarter began in 2009, 334,769 projects have been launched to date, but only 118,408 successfully reached their funding goals.

The success rate stands at 35.76 percent, a reminder that successfully completing a crowdfunding campaign is hardly a cakewalk. What’s more, a staggering 14 percent of projects completed campaigns without receiving a single pledge. For many creators, just getting noticed can be as much of a challenge as meeting the funding goal.

When it comes to crowdfunding, failure is the norm — but it doesn’t spell the end of a creator’s crowdfunding journey.

A post-mortem analysis might be painful but it can also prove invaluable, especially if a creator is keen to give crowdfunding another shot down the track. Identifying a campaign’s mistakes and pitfalls can highlight areas for improvement and, in some cases, allow the campaign to be resurrected and successfully funded.

Plenty of creators have endured setbacks and funding failures, only to rebound with vastly revamped campaigns. One example is artist and photographer Rob Decker and his National Parks Poster Project.

A Shaky Start

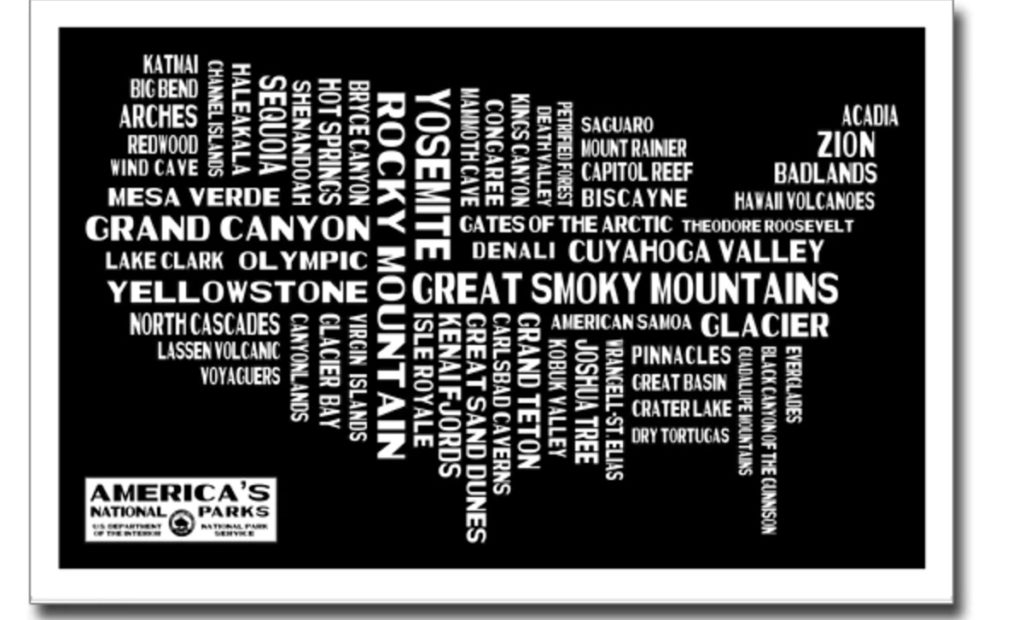

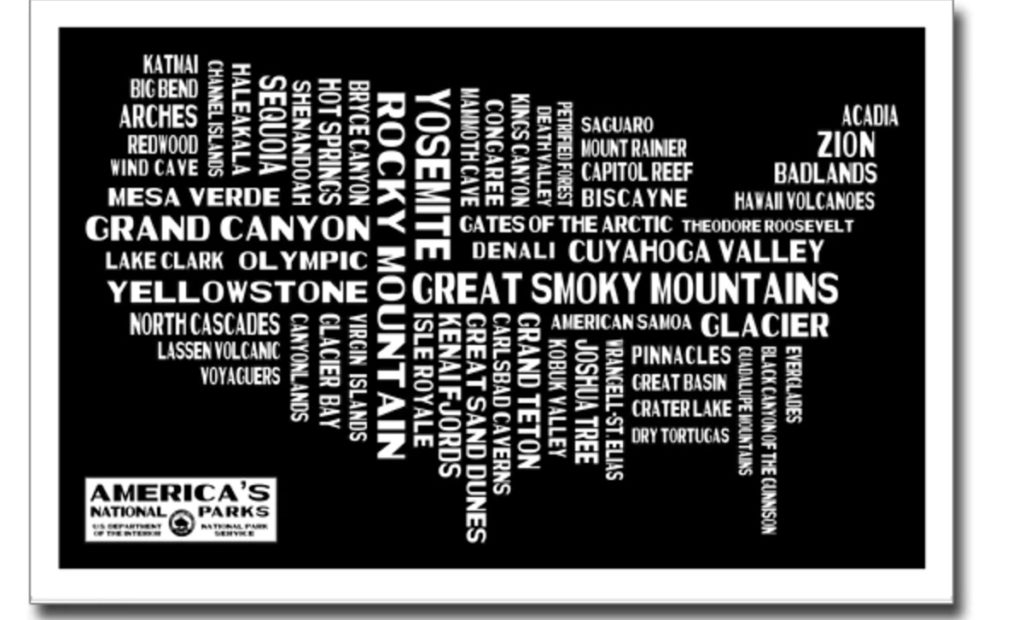

Decker’s ‘30s and ‘40s-style graphic art posters encapsulate the exquisite topography, stunning landscapes, and rich history of America’s national parks. They’re designed to appeal to outdoor enthusiasts, nature lovers, and the broader public alike.

Recently he’s been on a tear: three of his crowdfunding campaigns have raised enough money to fulfill his goals of creating an exclusive art collection designed to spark the public’s imagination.

Decker makes it look easy, but it’s important to remember that this wasn’t always the case. In fact, his first attempt at crowdfunding failed to reach its funding goal. For some, failure would be a deterrent, but it energized Decker’s crowdfunding efforts. Since the first campaign attempt in 2013, Decker has created three more campaigns on Kickstarter, with each one far exceeding its initial funding goal, raising between $20,000 and $30,000 per project.

What Went Wrong

Decker’s first crowdfunding campaign aimed to raise $27,000, but the goal eluded him. By the end of the campaign, 43 backers pledged a total of $5,370. Decker says there were a couple of flaws in his first crowdfunding attempt.

“I had set my funding goals too high,” he says. “Although I got a significant number of backers, I did fall short.”

A lack of outreach, compounded by a lack of social media promotion, loomed as another significant factor in the campaign’s failure. “I relied too heavily on my friends and family — my initial contact list — and also relied too much on what Kickstarter would bring to the mix,” he says. His use of social media was minimal — he admits he “didn’t really promote it” on any platform.

To promote his first campaign, Decker had a mailing list that comprised 1,000 or so contacts. It was a sizable number, but it wasn’t ambitious enough. In retrospect,” he says, “it wasn’t a big-enough list to generate the kind of funding I was looking for”.

New Campaigns, New Strategies

When it was time to relaunch his campaign, Decker decided to correct his early mistakes. First, he lowered his funding goal from $27,000 to $4,950, which gave him greater confidence that his efforts would be successful.

Then, Decker embraced social media to promote his crowdfunding efforts. He primarily used Facebook to spread the world, but also uploaded campaign videos to YouTube and posted promotional content on his Twitter and LinkedIn accounts, which helped to disseminate his message to a broader audience. The revitalized campaign ended up raising $23,120 from 373 backers.

A fresh pair of eyes can provide new perspective on the strengths and weaknesses of a campaign. Decker enlisted the assistance of a crowdfunding consultant and a publicist to tweak the focus of his successive campaigns.

Rethinking the Product

Restructuring the pledge rewards to make posters the main focus was the most important change. In the first campaign, backers had to pledge $40 to receive a National Parks poster; pledge tiers below that level offered rewards such as postcards, note cards, T-shirts and a calendar. Decker made the National Parks the core focus of the new campaign and made them available to backers at the $25 pledge tier. This decision proved immensely popular; the majority of backers chose this option in each of Decker’s three successful campaigns.

Decker also took the opportunity to focus his marketing copy. His first crowdfunding project was called ‘American Icons: Our National Parks’. He asked prospective backers to join him on a “journey to create iconic images for all 59 National Parks in a style reminiscent of the WPA from the 1930s and 1940s”. He used a simpler, catchier title for later campaigns: ‘The National Park Poster Project’. The tagline was similarly tightened: “An exclusive graphic art collection of America’s national parks … 35 years in the making.”

He also made some small but significant changes to the copy in the project’s ‘about’ section. Shortening the paragraphs and including images and infographics made the content more visually appealing.

Decker notes that although the National Parks Poster Project received little media coverage, focusing on a star product and having a cogent, engaging story defined the project’s appeal for backers. “It really did help shape the narrative,” Decker says. “It created a more singular message that better described the campaign and the project.”